On this day in 1431, peasant girl, national heroine of France, Catholic saint, The Maid of Orléans, Saint Joan of Arc was executed by burning in Rouen, France at the age of 19. Born around the year 1412 in Domrémy, a village which was then in the duchy of Bar (later annexed to the province of Lorraine and renamed Domrémy-la-Pucelle).

On this day in 1431, peasant girl, national heroine of France, Catholic saint, The Maid of Orléans, Saint Joan of Arc was executed by burning in Rouen, France at the age of 19. Born around the year 1412 in Domrémy, a village which was then in the duchy of Bar (later annexed to the province of Lorraine and renamed Domrémy-la-Pucelle).

Joan claimed divine guidance and led the French army to several important victories during the Hundred Years’ War, which paved the way for the coronation of Charles VII. She asserted that she had visions from God that instructed her to recover her homeland from English domination. The uncrowned Charles VII sent her to the siege of Orléans as part of a relief mission. She gained prominence when she overcame the dismissive attitude of veteran commanders and lifted the siege in only nine days. Several more swift victories led to Charles VII’s coronation at Reims and settled the disputed succession to the throne. She was captured by the Burgundians, sold to the English, tried and sentenced by an ecclesiastical court.

The Final Footprint – Joan’s ashes were cast into the Seine. A monument in Rouen dedicated to her is inscribed with the words of André Malraux: “O Jeanne, without sepulchre, without portrait, you know that the tomb of heroes is the heart of the living.” A statue in her honor was erected in the Notre Dame de Paris Cathedral, interior. Twenty-five years after the execution, Pope Callixtus III examined the trial, pronounced her innocent and declared her a martyr. Joan of Arc was beatified in 1909 and canonized in 1920. She is one of the patron saints of France, along with St. Denis, St. Martin of Tours, St. Louis IX, and St. Theresa of Lisieux.

The Final Footprint – Joan’s ashes were cast into the Seine. A monument in Rouen dedicated to her is inscribed with the words of André Malraux: “O Jeanne, without sepulchre, without portrait, you know that the tomb of heroes is the heart of the living.” A statue in her honor was erected in the Notre Dame de Paris Cathedral, interior. Twenty-five years after the execution, Pope Callixtus III examined the trial, pronounced her innocent and declared her a martyr. Joan of Arc was beatified in 1909 and canonized in 1920. She is one of the patron saints of France, along with St. Denis, St. Martin of Tours, St. Louis IX, and St. Theresa of Lisieux.

Down to the present day, Joan of Arc has remained a significant figure in Western culture. From Napoleon onward, French politicians of all leanings have invoked her memory. Writers and composers who have created works about her include: Shakespeare (Henry VI, Part 1), Voltaire (see below) (The Maid of Orleans poem), Schiller (The Maid of Orleans play), Verdi (Giovanna d’Arco), Tchaikovsky (The Maid of Orleans opera), Mark Twain (Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc), and George Bernard Shaw. Depictions of her continue in film, theatre, television, video games, music and performance.

On this day in 1593, playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era, Kit Marlowe, Christopher Marlowe, died in Deptford, Kent, England at the age of 29. Baptised 26 February 1564 in Canterbury, Kent, England. Marlowe was the foremost Elizabethan tragedian of his day. He greatly influenced William Shakespeare, who was born in the same year as Marlowe and who rose to become the pre-eminent Elizabethan playwright after Marlowe’s mysterious early death. Marlowe’s plays are known for the use of blank verse and their overreaching protagonists.

On this day in 1593, playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era, Kit Marlowe, Christopher Marlowe, died in Deptford, Kent, England at the age of 29. Baptised 26 February 1564 in Canterbury, Kent, England. Marlowe was the foremost Elizabethan tragedian of his day. He greatly influenced William Shakespeare, who was born in the same year as Marlowe and who rose to become the pre-eminent Elizabethan playwright after Marlowe’s mysterious early death. Marlowe’s plays are known for the use of blank verse and their overreaching protagonists.

A warrant was issued for Marlowe’s arrest on 18 May 1593. No reason was given for it, though it was thought to be connected to allegations of blasphemy—a manuscript believed to have been written by Marlowe was said to contain “vile heretical conceipts”. On 20 May, he was brought to the court to attend upon the Privy Council for questioning. There is no record of their having met that day, however, and he was commanded to attend upon them each day thereafter until “licensed to the contrary”. Ten days later, he was stabbed to death by Ingram Frizer. Whether or not the stabbing was connected to his arrest remains unknown.

Marlowe’s first play performed on the regular stage in London, in 1587, was Tamburlaine the Great, about the conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), who rises from shepherd to warlord. It is among the first English plays in blank verse, and, with Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy, generally is considered the beginning of the mature phase of the Elizabethan theatre. Tamburlaine was a success, and was followed with Tamburlaine the Great, Part II.

The two parts of Tamburlaine were published in 1590; all Marlowe’s other works were published posthumously. The sequence of the writing of his other four plays is unknown; all deal with controversial themes.

- The Jew of Malta (first published as The Famous Tragedy of the Rich Jew of Malta), about the Jew Barabas’ barbarous revenge against the city authorities, has a prologue delivered by a character representing Machiavelli. It was probably written in 1589 or 1590, and was first performed in 1592. It was a success, and remained popular for the next fifty years. The play was entered in the Stationers’ Register on 17 May 1594, but the earliest surviving printed edition is from 1633.

- Edward the Second is an English history play about the deposition of King Edward II by his barons and the Queen, who resent the undue influence the king’s favourites have in court and state affairs. The play was entered into the Stationers’ Register on 6 July 1593, five weeks after Marlowe’s death. The full title of the earliest extant edition, of 1594, is The troublesome reigne and lamentable death of Edward the second, King of England, with the tragicall fall of proud Mortimer.

- The Massacre at Paris is a short and luridly written work, the only surviving text of which was probably a reconstruction from memory of the original performance text, portraying the events of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572, which English Protestants invoked as the blackest example of Catholic treachery. It features the silent “English Agent”, whom subsequent tradition has identified with Marlowe himself and his connections to the secret service. The Massacre at Paris is considered his most dangerous play, as agitators in London seized on its theme to advocate the murders of refugees from the low countries and, indeed, it warns Elizabeth I of this possibility in its last scene. Its full title was The Massacre at Paris: With the Death of the Duke of Guise.

- Doctor Faustus (or The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus), based on the German Faustbuch, was the first dramatised version of the Faust legend of a scholar’s dealing with the devil. While versions of “The Devil’s Pact” can be traced back to the 4th century, Marlowe deviates significantly by having his hero unable to “burn his books” or repent to a merciful God in order to have his contract annulled at the end of the play. Marlowe’s protagonist is instead carried off by demons, and in the 1616 quarto his mangled corpse is found by several scholars.

The Final Footprint

Marlowe was buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St Nicholas, Deptford. The plaque shown here is modern.

Marlowe was buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Deptford immediately after the inquest, on 1 June 1593.

The mightiest kings have had their minions;

Great Alexander loved Hephaestion,

The conquering Hercules for Hylas wept;

And for Patroclus, stern Achilles drooped.

And not kings only, but the wisest men:

The Roman Tully loved Octavius,

Grave Socrates, wild Alcibiades.

The Muse of Poetry, part of the Marlowe Memorial in Canterbury

A Marlowe Memorial in the form of a bronze sculpture of The Muse of Poetry by Edward Onslow Ford was erected by subscription in Buttermarket, Canterbury in 1891.

In July 2002, a memorial window to Marlowe – a gift of the Marlowe Society – was unveiled in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey.

Come live with me and be my Love,

And we will all the pleasures prove

That hills and valleys, dales and fields,

Or woods or steepy mountain yields.

And we will sit upon the rocks,

And see the shepherds feed their flocks

By shallow rivers, to whose falls

Melodious birds sing madrigals.

And I will make thee beds of roses

And a thousand fragrant posies.

- The Passionate Shepherd to His Love (unknown date)

Che serà, serà:

What will be, shall be.

- Faustus, Act I, scene i, lines 47–58

- Hell hath no limits, nor is circumscrib’d

In one self place; but where we are is hell,

And where hell is, there must we ever be.

- Mephistopheles, Act II, scene i, line 118

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss!

- Faustus, Act V, scene i, lines 91–93

On this day in 1640, Flemish Baroque painter, Pieter Paul Rubens died in Antwerp at the age of 62 from heart failure, which was a result of his chronic gout. born in Siegen in Germany on 28 June 1577.

On this day in 1640, Flemish Baroque painter, Pieter Paul Rubens died in Antwerp at the age of 62 from heart failure, which was a result of his chronic gout. born in Siegen in Germany on 28 June 1577.

His unique and popular Baroque style emphasized movement, colour, and sensuality, which followed the immediate, dramatic artistic style promoted in the Counter-Reformation. Rubens specialized in making altarpieces, portraits, landscapes, and history paintings of mythological and allegorical subjects.

In addition to running a large studio in Antwerp that produced paintings popular with nobility and art collectors throughout Europe, Rubens was a classically educated humanist scholar and diplomat who was knighted by both Philip IV of Spain and Charles I of England. Rubens was a prolific artist. The catalogue of his works by Michael Jaffé lists 1,403 pieces, excluding numerous copies made in his workshop. The Museo del Prado owns the largest collection of Rubens’ paintings, and one of the finest as well, and almost all of it comes from Spain’s royal collections.

Gallery

- Early paintings

-

Portrait of a Young Woman with a Rosary, 1609–10, oil on wood, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

-

Venus at the Mirror, 1613–14, oil-painting, private collection

-

Diana Returning from Hunt, 1615, oil on canvas, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

-

The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus, c. 1617, oil on canvas, Alte Pinakothek

- Historical portraits

-

Portrait of Marchesa Brigida Spinola-Doria, 1606

-

Portrait of King Philip IV of Spain, c. 1628/1629

-

Portrait of Elisabeth of France. 1628, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Vienna

-

Portrait of Ambrogio Spinola, c. 1627 National Gallery in Prague

- Landscapes

-

Landscape with the Ruins of Mount Palatine in Rome, 1615

-

Miracle of Saint Hubert, painted together with Jan Bruegel, 1617

-

Landscape with Milkmaids and Cattle, 1618

-

The Château Het Steen with Hunter, c. 1635–1638 (National Gallery, London)

- Mythological

-

-

Jupiter and Callisto, 1613, Museumslandschaft of Hesse in Kassel

-

Pythagoras Advocating Vegetarianism, 1618–1630, by Rubens and Frans Snyders, inspired by Pythagoras’s speech in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Royal Collection.

- Nude

-

Susanna and the Elders, 1608

-

Ermit and sleeping Angelica, 1628

-

Susanna and the elders, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando.

- Helena Fourment and related pictures

-

Rubens with Hélène Fourment and their son Peter Paul, 1639, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Helena Fourment in Wedding Dress, detail, the artist’s second wife, c. 1630, now in the Alte Pinakothek

-

Bathsheba at the Fountain, 1635

-

-

The Night, 1601–1603, black chalk and gouache on paper (after Michelangelo), Louvre-Lens

-

Man in Korean Costume, c. 1617, black chalk with touches of red chalk, J. Paul Getty Museum

-

Peter Paul Rubens (possibly his self-portrait), c. 1620s

-

Young Woman with Folded Hands, c. 1629–30, red and black chalk, heightened with white, Boijmans Van Beuningen

-

Study of Three Women (Psyche and her sisters), c. 1635, sanguine and ink on paper, Warsaw University Library

-

Study for a St. Mary Magdalen, date unknown, British Museum

The Final Footprint – Rubens was interred in Saint Jacob’s church, Antwerp.

On this day in 1744, English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer and for his use of the heroic couplet, Alexander Pope died at the age of 56 in his villa in Twickenham surrounded by friends.

On this day in 1744, English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer and for his use of the heroic couplet, Alexander Pope died at the age of 56 in his villa in Twickenham surrounded by friends.

Perhaps best known for his satirical and discursive poetry, including The Rape of the Lock, The Dunciad, and An Essay on Criticism, as well as for his translation of Homer. After Shakespeare, Pope is the second-most quoted writer in the English language, per The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, some of his verses having even become popular idioms in common parlance (e.g., Damning with faint praise).

Pope’s poetic career testifies to his indomitable spirit in the face of disadvantages, of health and of circumstance. The poet and his family were Catholics and thus fell subject to the Test Acts, prohibitive measures which severely hampered the prosperity of their co-religionists after the abdication of James II; one of these banned them from living within ten miles of London, and another from attending public school or university. He was taught to read by his aunt and became a lover of books. He learned French, Italian, Latin, and Greek by himself, and discovered Homer at the age of six. As a child Pope survived being once trampled by a cow, but when he was 12 began struggling with tuberculosis of the spine (Pott disease), along with fits of crippling headaches which troubled him throughout his life.

In the year 1709, Pope showcased his precocious metrical skill with the publication of Pastorals, his first major poems. They earned him instant fame. By the time he was 23 he had written An Essay on Criticism, released in 1711. A kind of poetic manifesto in the vein of Horace’s Ars Poetica, the essay was met with enthusiastic attention.

The Rape of the Lock, perhaps the poet’s most famous poem, appeared first in 1712, followed by a revised and enlarged version in 1714. When Lord Petre forcibly snipped off a lock from Miss Arabella Fermor’s head (the “Belinda” of the poem), the incident gave rise to a high-society quarrel between the families. With the idea of allaying this, Pope treated the subject in a playful and witty mock-heroic epic. The narrative poem brings into focus the onset of acquisitive individualism and conspicuous consumption, where purchased goods assume dominance over moral agency.

A folio comprising a collection of his poems appeared in 1717, together with two new ones written about the passion of love. These were Verses to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady and the famous proto-romantic poem Eloisa to Abelard. Though Pope never married, about this time he became strongly attached to Lady M. Montagu, whom he indirectly referenced in the popular poem Eloisa to Abelard, and to Martha Blount, with whom his friendship continued throughout his life.

As his health was failing, and when told by his physician, on the morning of his death, that he was better, Pope replied: “Here am I, dying of a hundred good symptoms”.

The Final Footprint – He lies buried in the nave of the Church of St Mary the Virgin in Twickenham. In his will Pope asked to be carried at his funeral by 6 of the poorest men of Twickenham, kitted out in grey mourning suits; his manuscripts & publications he left to Lord Bolingbroke “either to be preserved or destroyed”. His epitaph in Latin; Qui nil molitur inepte, in nothing was he inept.

The Final Footprint – He lies buried in the nave of the Church of St Mary the Virgin in Twickenham. In his will Pope asked to be carried at his funeral by 6 of the poorest men of Twickenham, kitted out in grey mourning suits; his manuscripts & publications he left to Lord Bolingbroke “either to be preserved or destroyed”. His epitaph in Latin; Qui nil molitur inepte, in nothing was he inept.

On this day in 1778, French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, freedom of expression, free trade and separation of church and state, Voltaire died in Paris at the age of 83. Born François-Marie Arouet in Paris either on 21 November 1694 or 20 February 1694. Voltaire was a versatile writer, producing works in almost every literary form, including plays, poems, novels, essays, and historical and scientific works. He wrote more than 20,000 letters and more than 2,000 books and pamphlets. He was an outspoken advocate, despite the risk this placed him in under the strict censorship laws of the time. As a satirical polemicist, he frequently made use of his works to criticize intolerance, religious dogma, and the French institutions of his day.

On this day in 1778, French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, freedom of expression, free trade and separation of church and state, Voltaire died in Paris at the age of 83. Born François-Marie Arouet in Paris either on 21 November 1694 or 20 February 1694. Voltaire was a versatile writer, producing works in almost every literary form, including plays, poems, novels, essays, and historical and scientific works. He wrote more than 20,000 letters and more than 2,000 books and pamphlets. He was an outspoken advocate, despite the risk this placed him in under the strict censorship laws of the time. As a satirical polemicist, he frequently made use of his works to criticize intolerance, religious dogma, and the French institutions of his day.

The Final Footprint – Because of his well-known criticism of the Church, which he had refused to retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial, but friends managed to bury his body secretly at the Abbey of Scellières in Champagne before this prohibition had been announced. His heart and brain were embalmed separately. On 11 July 1791, the National Assembly of France, which regarded him as a forerunner of the French Revolution, had his remains brought back to Paris to enshrine him in the Panthéon. It is estimated that a million people attended the procession, which stretched throughout Paris. There was an elaborate ceremony, complete with an orchestra, and the music included a piece that André Grétry had composed specially for the event. A widely repeated story, that the remains of Voltaire were stolen by religious fanatics in 1814 or 1821 during the Pantheon restoration and thrown into a garbage heap, is false. Such rumours resulted in the coffin being opened in 1897, which confirmed that his remains were still present. Other notable Final Footprints at the Panthéon include: Louis Braille, Pierre and Marie Curie, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, André Malraux, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Émile Zola.

The Final Footprint – Because of his well-known criticism of the Church, which he had refused to retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial, but friends managed to bury his body secretly at the Abbey of Scellières in Champagne before this prohibition had been announced. His heart and brain were embalmed separately. On 11 July 1791, the National Assembly of France, which regarded him as a forerunner of the French Revolution, had his remains brought back to Paris to enshrine him in the Panthéon. It is estimated that a million people attended the procession, which stretched throughout Paris. There was an elaborate ceremony, complete with an orchestra, and the music included a piece that André Grétry had composed specially for the event. A widely repeated story, that the remains of Voltaire were stolen by religious fanatics in 1814 or 1821 during the Pantheon restoration and thrown into a garbage heap, is false. Such rumours resulted in the coffin being opened in 1897, which confirmed that his remains were still present. Other notable Final Footprints at the Panthéon include: Louis Braille, Pierre and Marie Curie, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, André Malraux, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Émile Zola.

#RIP #OTD in 1960 poet (My Sister, Life), novelist (Doctor Zhivago), literary translator Boris Pasternak died of lung cancer in his dacha in Peredelkino near Mosscow, aged 70. Peredelkino Cemetery

#RIP #OTD in 1967 actor (The Invisible Man, The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Wolf Man, Casablanca, Kings Row, Notorious, Lawrence of Arabia) Claude Rains died from cirrhosis of the liver, aged 77. Red Hill Cemetery in Moultonborough, New Hampshire

#RIP #OTD in 1993 jazz composer, bandleader, piano and synthesizer player, poet, Sun Ra died at Princeton Baptist Medical Center, Birmingham, Alabama, aged 79. Elmwood Cemetery, Birmingham

Have you planned yours yet?

Follow TFF on twitter @RIPPTFF

On this day in 1519, daughter of Pope Alexander VI, Lady of Pesaro and Gradara, Duchess of Bisceglie and Princess of Salerno, Duchess of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio, Lucrezia Borgia died in Ferrara, Italy at the age of 39 from complications after giving birth to her eighth child, having had a lifelong history of complicated pregnancies and miscarriages. Born in Subiaco, near Rome on 18 April 1480. Her mother was Vannozza dei Cattanei, one of the mistresses of Lucrezia’s father, Rodrigo Borgia (Pope Alexander VI). Her brothers included Cesare Borgia, Giovanni Borgia, and Gioffre Borgia. Lucrezia’s family later came to epitomize the ruthless Machiavellian politics and sexual corruption characteristic of the Renaissance Papacy. Lucrezia was cast as a femme fatale, a role she has been portrayed as in many artworks, novels, films and an opera. Very little is known of Lucrezia, and the extent of her complicity in the political machinations of her father and brothers is unclear. They certainly arranged several marriages for her to important or powerful men in order to advance their own political ambitions. Lucrezia was married to Giovanni Sforza (Lord of Pesaro), Alfonso of Aragon (Duke of Bisceglie), and Alfonso I d’Este (Duke of Ferrara). Tradition has it that Alfonso of Aragon was an illegitimate son of the King of Naples and that Lucrezia’s brother Cesare may have had him murdered after his political value waned.

On this day in 1519, daughter of Pope Alexander VI, Lady of Pesaro and Gradara, Duchess of Bisceglie and Princess of Salerno, Duchess of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio, Lucrezia Borgia died in Ferrara, Italy at the age of 39 from complications after giving birth to her eighth child, having had a lifelong history of complicated pregnancies and miscarriages. Born in Subiaco, near Rome on 18 April 1480. Her mother was Vannozza dei Cattanei, one of the mistresses of Lucrezia’s father, Rodrigo Borgia (Pope Alexander VI). Her brothers included Cesare Borgia, Giovanni Borgia, and Gioffre Borgia. Lucrezia’s family later came to epitomize the ruthless Machiavellian politics and sexual corruption characteristic of the Renaissance Papacy. Lucrezia was cast as a femme fatale, a role she has been portrayed as in many artworks, novels, films and an opera. Very little is known of Lucrezia, and the extent of her complicity in the political machinations of her father and brothers is unclear. They certainly arranged several marriages for her to important or powerful men in order to advance their own political ambitions. Lucrezia was married to Giovanni Sforza (Lord of Pesaro), Alfonso of Aragon (Duke of Bisceglie), and Alfonso I d’Este (Duke of Ferrara). Tradition has it that Alfonso of Aragon was an illegitimate son of the King of Naples and that Lucrezia’s brother Cesare may have had him murdered after his political value waned. The Final Footprint – Lucrezia was entombed in the convent of Corpus Domini. On 15 October 1816, the Romantic poet Lord Byron visited the Ambrosian Library of Milan. He was delighted by the letters between Borgia and her one-time lover, poet Pietro Bembo (“The prettiest love letters in the world”) and claimed to have managed to steal a lock of her hair (“the prettiest and fairest imaginable”) held on display. Victor Hugo’s 1833 stage play Lucrèce Borgia, loosely based on the stories of Lucrezia, was transformed into a libretto by Felice Romani for Donizetti’s opera, Lucrezia Borgia (1834), first performed at La Scala, Milan, 26 December 1834.

The Final Footprint – Lucrezia was entombed in the convent of Corpus Domini. On 15 October 1816, the Romantic poet Lord Byron visited the Ambrosian Library of Milan. He was delighted by the letters between Borgia and her one-time lover, poet Pietro Bembo (“The prettiest love letters in the world”) and claimed to have managed to steal a lock of her hair (“the prettiest and fairest imaginable”) held on display. Victor Hugo’s 1833 stage play Lucrèce Borgia, loosely based on the stories of Lucrezia, was transformed into a libretto by Felice Romani for Donizetti’s opera, Lucrezia Borgia (1834), first performed at La Scala, Milan, 26 December 1834. On this day in 1987 comedian, actor and musician Jackie Gleason died at his home in Lauderhill, Florida at the age of 71. Born Herbert Walton Gleason, Jr. on 26 February 1916 in either Bushwick or Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. Perhaps best known for his role on television as Ralph Kramden in The Honeymooners and for The Jackie Gleason Show (1952-1970). His most noted film roles were as Minnesota Fats in the drama film The Hustler (1961) starring Paul Newman, and as Buford T. Justice in the Smokey and the Bandit movie series. Gleason married three times; Genevieve Halford (1936-1970 divorce), Beverly McKittrick (1970-1975 divorce) and Marilyn Taylor (1975-1987 his death). His trademark phrases were “And away we go!” and “How sweet it is!”. In my opinion, The Honymooners is, without question, the “Bang, Zoom” funniest show that ever aired on television. And I will stand on Jerry Seinfeld’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say that. I remember watching The Jackie Gleason Show as a kid. Gleason was hilarious in Smokey and the Bandit.

On this day in 1987 comedian, actor and musician Jackie Gleason died at his home in Lauderhill, Florida at the age of 71. Born Herbert Walton Gleason, Jr. on 26 February 1916 in either Bushwick or Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. Perhaps best known for his role on television as Ralph Kramden in The Honeymooners and for The Jackie Gleason Show (1952-1970). His most noted film roles were as Minnesota Fats in the drama film The Hustler (1961) starring Paul Newman, and as Buford T. Justice in the Smokey and the Bandit movie series. Gleason married three times; Genevieve Halford (1936-1970 divorce), Beverly McKittrick (1970-1975 divorce) and Marilyn Taylor (1975-1987 his death). His trademark phrases were “And away we go!” and “How sweet it is!”. In my opinion, The Honymooners is, without question, the “Bang, Zoom” funniest show that ever aired on television. And I will stand on Jerry Seinfeld’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say that. I remember watching The Jackie Gleason Show as a kid. Gleason was hilarious in Smokey and the Bandit. The Final Footprint – Gleason is entombed in a private mausoleum in Our Lady of Mercy Catholic Cemetery in Miami, Florida. Engraved at the base of the mausoleum is his epitaph; “AND AWAY WE GO”. A life-size statue of Gleason, in full uniform as bus driver Ralph Kramden, stands outside the Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York City. Another statue stands at the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Hall of Fame in North Hollywood, California, showing Gleason in his famous “And away we go!” pose. Local signs on the Brooklyn Bridge, which indicate to drivers that they are entering Brooklyn, have the Gleason phrase “How Sweet It Is!” as part of the sign.

The Final Footprint – Gleason is entombed in a private mausoleum in Our Lady of Mercy Catholic Cemetery in Miami, Florida. Engraved at the base of the mausoleum is his epitaph; “AND AWAY WE GO”. A life-size statue of Gleason, in full uniform as bus driver Ralph Kramden, stands outside the Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York City. Another statue stands at the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Hall of Fame in North Hollywood, California, showing Gleason in his famous “And away we go!” pose. Local signs on the Brooklyn Bridge, which indicate to drivers that they are entering Brooklyn, have the Gleason phrase “How Sweet It Is!” as part of the sign. On this day in 2014, actor, graduate of the University of Texas, Eli Wallach died of natural causes at the age of 98 in Manhattan. Born Eli Herschel Wallach on 7 December 1915 in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Wallach’s career spanned more than six decades, beginning in the late 1940s. On stage, he often co-starred with his wife, Anne Jackson, becoming one of the best-known acting couples in the American theater. Wallach initially studied method acting under Sanford Meisner, and later became a founding member of the Actors Studio, where he studied under Lee Strasberg. His versatility gave him the ability to play a wide variety of different roles throughout his career, primarily as a supporting actor.

On this day in 2014, actor, graduate of the University of Texas, Eli Wallach died of natural causes at the age of 98 in Manhattan. Born Eli Herschel Wallach on 7 December 1915 in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Wallach’s career spanned more than six decades, beginning in the late 1940s. On stage, he often co-starred with his wife, Anne Jackson, becoming one of the best-known acting couples in the American theater. Wallach initially studied method acting under Sanford Meisner, and later became a founding member of the Actors Studio, where he studied under Lee Strasberg. His versatility gave him the ability to play a wide variety of different roles throughout his career, primarily as a supporting actor.

On this day in 1799, attorney, planter, politician, orator, and Founding Father, Patrick Henry died of stomach cancer at Red Hill, his plantation near Brookneal, Virginia at the age of 63. Born 29 May 1736 in Hanover County, Virginia. Remembered for his “Give me Liberty, or give me Death!” speech.

On this day in 1799, attorney, planter, politician, orator, and Founding Father, Patrick Henry died of stomach cancer at Red Hill, his plantation near Brookneal, Virginia at the age of 63. Born 29 May 1736 in Hanover County, Virginia. Remembered for his “Give me Liberty, or give me Death!” speech.

On this day in 1968, politician, civil rights activist, RFK, Robert F. Kennedy died at Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles from gunshot wounds sustained at The Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles at the age of 42. Born Robert Francis Kennedy on 20 November 1925 in Brookline, Massachusetts. He was the younger brother of John F. Kennedy and the older brother of Edward M. Kennedy. RFK was a graduate of Harvard and obtained his law degree from the University of Virginia. He served as Attorney General of the United States (1961-1964) first under his brother, JFK, then briefly under LBJ. Following JFK’s assassination, at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, RFK quoted Shakespeare (from Romeo and Juliet) in speaking of his brother;

On this day in 1968, politician, civil rights activist, RFK, Robert F. Kennedy died at Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles from gunshot wounds sustained at The Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles at the age of 42. Born Robert Francis Kennedy on 20 November 1925 in Brookline, Massachusetts. He was the younger brother of John F. Kennedy and the older brother of Edward M. Kennedy. RFK was a graduate of Harvard and obtained his law degree from the University of Virginia. He served as Attorney General of the United States (1961-1964) first under his brother, JFK, then briefly under LBJ. Following JFK’s assassination, at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, RFK quoted Shakespeare (from Romeo and Juliet) in speaking of his brother; The Final Footprint – His body was returned to New York City, where it lay in repose at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral for several days before the Requiem Mass held there on June 8. His brother, Ted, eulogized him with the words:

The Final Footprint – His body was returned to New York City, where it lay in repose at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral for several days before the Requiem Mass held there on June 8. His brother, Ted, eulogized him with the words: On this day in 1982, poet, translator, essayist, “The Father of the Beats”, Kenneth Rexroth died in Santa Barbara, California at the age of 76. Born Kenneth Charles Marion Rexroth in South Bend, Indiana on 22 December 1905. In my opinion, one of the central figures in the San Francisco Renaissance. Although he apparently did not consider himself to be a Beat poet, and disliked the association, he was dubbed the “Father of the Beats” by Time. He was among the first poets in the United States to explore traditional Japanese poetic forms such as haiku. Much of Rexroth’s work can be classified as “erotic” or “love poetry,” given his deep fascination with transcendent love. Rexroth married four times; Andrée Dutcher (1927-1940), Marie Kass (1941-1955), Marthe Larsen (1949- ), Carol Tinker ( – 1982 his death).

On this day in 1982, poet, translator, essayist, “The Father of the Beats”, Kenneth Rexroth died in Santa Barbara, California at the age of 76. Born Kenneth Charles Marion Rexroth in South Bend, Indiana on 22 December 1905. In my opinion, one of the central figures in the San Francisco Renaissance. Although he apparently did not consider himself to be a Beat poet, and disliked the association, he was dubbed the “Father of the Beats” by Time. He was among the first poets in the United States to explore traditional Japanese poetic forms such as haiku. Much of Rexroth’s work can be classified as “erotic” or “love poetry,” given his deep fascination with transcendent love. Rexroth married four times; Andrée Dutcher (1927-1940), Marie Kass (1941-1955), Marthe Larsen (1949- ), Carol Tinker ( – 1982 his death). The Final Footprint – Rexroth is interred on the grounds of the Santa Barbara Cemetery Association overlooking the sea. While all the other graves face inland, his alone faces the Pacific. His epitaph reads, “As the full moon rises / The swan sings in sleep / On the lake of the mind.” According to association records, he is interred near the corner of Island and Bluff boulevards, in Block C of the Sunset section, Plot 18. Other notable Final Footprints at Santa Barbara include actor Laurence Harvey, Fess Parker, and Suzy Parker (no relation to Fess).

The Final Footprint – Rexroth is interred on the grounds of the Santa Barbara Cemetery Association overlooking the sea. While all the other graves face inland, his alone faces the Pacific. His epitaph reads, “As the full moon rises / The swan sings in sleep / On the lake of the mind.” According to association records, he is interred near the corner of Island and Bluff boulevards, in Block C of the Sunset section, Plot 18. Other notable Final Footprints at Santa Barbara include actor Laurence Harvey, Fess Parker, and Suzy Parker (no relation to Fess). On this day in 2006, musician and songwriter, the Fifth Beatle, Billy Preston died in Scottsdale, Arizona, of complications of malignant hypertension that resulted in kidney failure and other complications at the age of 59. Born William Everett Preston on 2 September 1946 in Houston. Preston became famous first as a session musician with artists such as Little Richard, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles and the Beatles, and was later successful as a solo artist with hit pop singles including “Outa-Space”, its sequel, “Space Race”, “Will It Go Round in Circles” and “Nothing from Nothing”, and a string of albums and guest appearances with Eric Clapton, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and others. In addition, Preston was co-author, with The Beach Boys’ Dennis Wilson, of “You Are So Beautiful,” recorded by Preston and later a #5 hit for Joe Cocker.

On this day in 2006, musician and songwriter, the Fifth Beatle, Billy Preston died in Scottsdale, Arizona, of complications of malignant hypertension that resulted in kidney failure and other complications at the age of 59. Born William Everett Preston on 2 September 1946 in Houston. Preston became famous first as a session musician with artists such as Little Richard, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles and the Beatles, and was later successful as a solo artist with hit pop singles including “Outa-Space”, its sequel, “Space Race”, “Will It Go Round in Circles” and “Nothing from Nothing”, and a string of albums and guest appearances with Eric Clapton, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and others. In addition, Preston was co-author, with The Beach Boys’ Dennis Wilson, of “You Are So Beautiful,” recorded by Preston and later a #5 hit for Joe Cocker. The Final Footprint – His funeral was held on June 20 at the Faithful Central Bible Church in Inglewood, California, where his remains were entombed at Inglewood Park Cemetery. Other notable Final Footprints at Inglewood Park include; Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, Betty Grable, Etta James, Robert Kardashian, Gypsy Rose Lee, Cesar Romero, Big Mama Thornton, T-Bone Walker, and Syreeta Wright.

The Final Footprint – His funeral was held on June 20 at the Faithful Central Bible Church in Inglewood, California, where his remains were entombed at Inglewood Park Cemetery. Other notable Final Footprints at Inglewood Park include; Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, Betty Grable, Etta James, Robert Kardashian, Gypsy Rose Lee, Cesar Romero, Big Mama Thornton, T-Bone Walker, and Syreeta Wright.

On this day in 1910, writer O. Henry died of cirrhosis of the liver, complications of diabetes, and an enlarged heart in New York City at the age of 47. Born William Sydney Porter on 11 September 1862 in Greensboro, North Carolina. O. Henry’s short stories are known for their wit, wordplay, warm characterization and clever twist endings. Among his most famous stories are: “The Gift of the Magi”, “The Ransom of Red Chief”, “The Cop and the Anthem”, “A Retrieved Reformation”, and “The Duplicity of Hargraves”.

On this day in 1910, writer O. Henry died of cirrhosis of the liver, complications of diabetes, and an enlarged heart in New York City at the age of 47. Born William Sydney Porter on 11 September 1862 in Greensboro, North Carolina. O. Henry’s short stories are known for their wit, wordplay, warm characterization and clever twist endings. Among his most famous stories are: “The Gift of the Magi”, “The Ransom of Red Chief”, “The Cop and the Anthem”, “A Retrieved Reformation”, and “The Duplicity of Hargraves”.

On this day in 1993, singer and songwriter Conway Twitty died in Springfield, Missouri, at Cox South Hospital, from an abdominal aortic aneurysm, aged 59. Born Harold Lloyd Jenkins on 1 September 1933 in Friars Point in Coahoma County in northwestern Mississippi. He held the record for the most number one singles of any act, with 40 No. 1 Billboard country hits, until George Strait broke the record in 2006. From 1971 to 1976, Twitty received a string of Country Music Association awards for duets with Loretta Lynn. Although never a member of the Grand Ole Opry, he was inducted into both the Country Music and Rockabilly Halls of Fame.

On this day in 1993, singer and songwriter Conway Twitty died in Springfield, Missouri, at Cox South Hospital, from an abdominal aortic aneurysm, aged 59. Born Harold Lloyd Jenkins on 1 September 1933 in Friars Point in Coahoma County in northwestern Mississippi. He held the record for the most number one singles of any act, with 40 No. 1 Billboard country hits, until George Strait broke the record in 2006. From 1971 to 1976, Twitty received a string of Country Music Association awards for duets with Loretta Lynn. Although never a member of the Grand Ole Opry, he was inducted into both the Country Music and Rockabilly Halls of Fame.

On this day in 2004, radio, film and television actor, 33rd Governor of California, 40th President of the United States, Dutch, Ronald Reagan died at his home in Bel Air, California of Alzheimer’s disease at the age of 93. Born Ronald Wilson Reagan on 6 February 2011 in Tampico, Illinois. His father was the descendant of Irish Catholic immigrants from County Tipperary while his mother had Scots-English ancestors. His father nicknamed him Dutch after his Dutchboy haircut.

On this day in 2004, radio, film and television actor, 33rd Governor of California, 40th President of the United States, Dutch, Ronald Reagan died at his home in Bel Air, California of Alzheimer’s disease at the age of 93. Born Ronald Wilson Reagan on 6 February 2011 in Tampico, Illinois. His father was the descendant of Irish Catholic immigrants from County Tipperary while his mother had Scots-English ancestors. His father nicknamed him Dutch after his Dutchboy haircut. The Final Footprint – Reagan’s body was taken to the Kingsley and Gates Funeral Home in Santa Monica, California where well-wishers paid tribute by laying flowers and American flags in the grass. On June 7, his body was removed and taken to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, where a brief family funeral was held. His body lay in repose in the Library lobby until June 9. Reagan’s body was then flown to Washington, D.C. where he became the tenth United States president to lie in state. On 11 June, a state funeral was conducted in the Washington National Cathedral, presided over by President George W. Bush. Eulogies were given by former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, and both Presidents Bush. Also in attendance were Gorbachev, and many world leaders, including British Prime Minister Tony Blair, German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, and interim presidents Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan, and Ghazi al-Yawer of Iraq. After the funeral, the Reagan entourage was flown back to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in California, where another service was held, and President Reagan was interred. His was the first state funeral in the United States since that of President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1973. His burial site is inscribed with the words he delivered at the opening of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library: ”

The Final Footprint – Reagan’s body was taken to the Kingsley and Gates Funeral Home in Santa Monica, California where well-wishers paid tribute by laying flowers and American flags in the grass. On June 7, his body was removed and taken to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, where a brief family funeral was held. His body lay in repose in the Library lobby until June 9. Reagan’s body was then flown to Washington, D.C. where he became the tenth United States president to lie in state. On 11 June, a state funeral was conducted in the Washington National Cathedral, presided over by President George W. Bush. Eulogies were given by former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, and both Presidents Bush. Also in attendance were Gorbachev, and many world leaders, including British Prime Minister Tony Blair, German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, and interim presidents Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan, and Ghazi al-Yawer of Iraq. After the funeral, the Reagan entourage was flown back to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in California, where another service was held, and President Reagan was interred. His was the first state funeral in the United States since that of President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1973. His burial site is inscribed with the words he delivered at the opening of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library: ” On this day in 2012, fantasy, science fiction, horror and mystery fiction writer, Ray Bradbury died in Los Angeles, California, at the age of 91, after a lengthy illness. Born Ray Douglas Bradbury on 22 August 1920 in Waukegan, Illinois. Perhaps best known for his dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953) and for the science fiction and horror stories gathered together as The Martian Chronicles (1950) and The Illustrated Man (1951). Bradbury was one of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers. Many of Bradbury’s works have been adapted into comic books, television shows and films.

On this day in 2012, fantasy, science fiction, horror and mystery fiction writer, Ray Bradbury died in Los Angeles, California, at the age of 91, after a lengthy illness. Born Ray Douglas Bradbury on 22 August 1920 in Waukegan, Illinois. Perhaps best known for his dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953) and for the science fiction and horror stories gathered together as The Martian Chronicles (1950) and The Illustrated Man (1951). Bradbury was one of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers. Many of Bradbury’s works have been adapted into comic books, television shows and films. The Final Footprint – Bradbury is interred at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery (a

The Final Footprint – Bradbury is interred at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery (a

On this day in 1875, composer and pianist of the Romantic era, Georges Bizet died on his sixth wedding anniversary, from heart failure at the age of 36 in Bougival (Yvelines), about 10 miles west of Paris. Born Georges Alexandre César Léopold Bizet on 25 October 1838 at 26 rue de la Tour d’Auvergne in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. Perhaps best know for his opera Carmen. Carmen, which is based on a novella of the same title written in 1846 by the French writer Prosper Mérimée, premiered on 3 March 1875, at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, but received an initial lukewarm reception. Bizet was reportedly bitterly disappointed. Of course, Carmen has since become one of the most popular works in the entire operatic repertoire. In June 1862 the Bizet family’s maid, Marie Reiter, gave birth to a son, Jean Bizet. Bizet married Geneviève Halévy (1869–1875 his death). Bravo Bizet! Dear reader, I strongly suggest you purchase/download Carmen and see it live when you can.

On this day in 1875, composer and pianist of the Romantic era, Georges Bizet died on his sixth wedding anniversary, from heart failure at the age of 36 in Bougival (Yvelines), about 10 miles west of Paris. Born Georges Alexandre César Léopold Bizet on 25 October 1838 at 26 rue de la Tour d’Auvergne in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. Perhaps best know for his opera Carmen. Carmen, which is based on a novella of the same title written in 1846 by the French writer Prosper Mérimée, premiered on 3 March 1875, at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, but received an initial lukewarm reception. Bizet was reportedly bitterly disappointed. Of course, Carmen has since become one of the most popular works in the entire operatic repertoire. In June 1862 the Bizet family’s maid, Marie Reiter, gave birth to a son, Jean Bizet. Bizet married Geneviève Halévy (1869–1875 his death). Bravo Bizet! Dear reader, I strongly suggest you purchase/download Carmen and see it live when you can. The Final Footprint – Bizet is entombed in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His tomb is marked by an upright marble or stone monument with his bronze bust on top. The names of his operas are engraved on the side of the monument. The following is engraved on the front; SA FAMILLE ET SES AMIS (His family and friends). Other notable Final Footprints at Père Lachaise include; Guillaume Apollinaire, Honoré de Balzac, Jean-Dominique Bauby, Maria Callas, Chopin, Colette, Auguste Comte, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Molière, Jim Morrison, Édith Piaf, Camille Pissarro, Marcel Proust, Sully Prudhomme, Gioachino Rossini, Georges-Pierre Seurat, Simone Signoret, Gertrude Stein, Dorothea Tanning, Alice B. Toklas, Oscar Wilde, and Richard Wright.

The Final Footprint – Bizet is entombed in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His tomb is marked by an upright marble or stone monument with his bronze bust on top. The names of his operas are engraved on the side of the monument. The following is engraved on the front; SA FAMILLE ET SES AMIS (His family and friends). Other notable Final Footprints at Père Lachaise include; Guillaume Apollinaire, Honoré de Balzac, Jean-Dominique Bauby, Maria Callas, Chopin, Colette, Auguste Comte, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Molière, Jim Morrison, Édith Piaf, Camille Pissarro, Marcel Proust, Sully Prudhomme, Gioachino Rossini, Georges-Pierre Seurat, Simone Signoret, Gertrude Stein, Dorothea Tanning, Alice B. Toklas, Oscar Wilde, and Richard Wright.

On this day in 1973, United States Navy veteran, professional wrestler, humanitarian, Dory Funk died at St. Anthony’s Hospital in Amarillo, Texas from a heart attack at the age of 54. Born Dorrance Wilhelm Funk on 4 May 1919 in Hammond, Indiana. Funk is the father of wrestlers Dory Funk, Jr. and Terry Funk. He founded The Double Cross Ranch near Amarillo. He was a long time supporter of the Cal Farley Boys Ranch. As a boy growing up in the Texas Panhandle, I watched the Funks wrestle on television. We called it “big time wrastlin'”.

On this day in 1973, United States Navy veteran, professional wrestler, humanitarian, Dory Funk died at St. Anthony’s Hospital in Amarillo, Texas from a heart attack at the age of 54. Born Dorrance Wilhelm Funk on 4 May 1919 in Hammond, Indiana. Funk is the father of wrestlers Dory Funk, Jr. and Terry Funk. He founded The Double Cross Ranch near Amarillo. He was a long time supporter of the Cal Farley Boys Ranch. As a boy growing up in the Texas Panhandle, I watched the Funks wrestle on television. We called it “big time wrastlin'”.

On this day in 1962, author, poet and one-time lover of Virginia Woolf, The Hon Victoria Mary Sackville-West, Lady Nicolson, died at the age of 70 in Sissinghurst Castle, Kent, England. Born Victoria Mary Sackville-West at Knole House near Sevenoaks, Kent on 9 March 1892. She won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927 and 1933. She was known for her exuberant aristocratic life, her passionate affair with the novelist Woolf, and Sissinghurst Castle Garden, which she and her husband, Sir Harold Nicolson, created at their estate. Woolf wrote one of her most famous novels, Orlando, described by Sackville-West’s son Nigel Nicolson as “the longest and most charming love-letter in literature”, as a result of her affair with Sackville-West. The moment of the conception of Orlando was documented from Woolf’s diary on 5 October 1927: “And instantly the usual exciting devices enter my mind: a biography beginning in the year 1500 and continuing to the present day, called Orlando: Vita; only with a change about from one sex to the other”.

On this day in 1962, author, poet and one-time lover of Virginia Woolf, The Hon Victoria Mary Sackville-West, Lady Nicolson, died at the age of 70 in Sissinghurst Castle, Kent, England. Born Victoria Mary Sackville-West at Knole House near Sevenoaks, Kent on 9 March 1892. She won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927 and 1933. She was known for her exuberant aristocratic life, her passionate affair with the novelist Woolf, and Sissinghurst Castle Garden, which she and her husband, Sir Harold Nicolson, created at their estate. Woolf wrote one of her most famous novels, Orlando, described by Sackville-West’s son Nigel Nicolson as “the longest and most charming love-letter in literature”, as a result of her affair with Sackville-West. The moment of the conception of Orlando was documented from Woolf’s diary on 5 October 1927: “And instantly the usual exciting devices enter my mind: a biography beginning in the year 1500 and continuing to the present day, called Orlando: Vita; only with a change about from one sex to the other”.

On this day in 1246, queen consort of England as the second wife of King John, from 1200 until John’s death in 1216, renowned beauty, the “Helen” of the Middle Ages, and mother of the future King Henry III, Isabella of Angoulême died at Fontevraud Abbey in France at the approximate age of 57.

On this day in 1246, queen consort of England as the second wife of King John, from 1200 until John’s death in 1216, renowned beauty, the “Helen” of the Middle Ages, and mother of the future King Henry III, Isabella of Angoulême died at Fontevraud Abbey in France at the approximate age of 57. On this day in 1809, composer, “Father of the Symphony” and “Father of the String Quartet”, Joseph Haydn died at his home in the Vienna suburb of Gumpendorf, at the age of 77. Born Franz Joseph Haydn on 31 March 1732 in Rohrau, Austria.

On this day in 1809, composer, “Father of the Symphony” and “Father of the String Quartet”, Joseph Haydn died at his home in the Vienna suburb of Gumpendorf, at the age of 77. Born Franz Joseph Haydn on 31 March 1732 in Rohrau, Austria. The Final Footprint – Some of his last words reportedly were attempts to calm and reassure his servants as the French army under Napoleon launched an attack on Vienna: “My children, have no fear, for where Haydn is, no harm can fall.” On 15 June 1809, a memorial service was held in the Schottenkirche at which Mozart’s Requiem was performed. Haydn’s remains were interred in the local Hundsturm cemetery until 1820, when they were moved to the Bergkirche in Eisenstadt, Austria by Prince Nikolaus. His head took a different journey; it was stolen by phrenologists shortly after burial, and the skull was reunited with the other remains only in 1954.

The Final Footprint – Some of his last words reportedly were attempts to calm and reassure his servants as the French army under Napoleon launched an attack on Vienna: “My children, have no fear, for where Haydn is, no harm can fall.” On 15 June 1809, a memorial service was held in the Schottenkirche at which Mozart’s Requiem was performed. Haydn’s remains were interred in the local Hundsturm cemetery until 1820, when they were moved to the Bergkirche in Eisenstadt, Austria by Prince Nikolaus. His head took a different journey; it was stolen by phrenologists shortly after burial, and the skull was reunited with the other remains only in 1954. On this day in 1431, peasant girl, national heroine of France, Catholic saint, The Maid of Orléans, Saint Joan of Arc was executed by burning in Rouen, France at the age of 19. Born around the year 1412 in Domrémy, a village which was then in the duchy of Bar (later annexed to the province of Lorraine and renamed Domrémy-la-Pucelle).

On this day in 1431, peasant girl, national heroine of France, Catholic saint, The Maid of Orléans, Saint Joan of Arc was executed by burning in Rouen, France at the age of 19. Born around the year 1412 in Domrémy, a village which was then in the duchy of Bar (later annexed to the province of Lorraine and renamed Domrémy-la-Pucelle). The Final Footprint – Joan’s ashes were cast into the Seine. A monument in Rouen dedicated to her is inscribed with the words of André Malraux: “O Jeanne, without sepulchre, without portrait, you know that the tomb of heroes is the heart of the living.” A statue in her honor was erected in the Notre Dame de Paris Cathedral, interior. Twenty-five years after the execution, Pope Callixtus III examined the trial, pronounced her innocent and declared her a martyr. Joan of Arc was beatified in 1909 and canonized in 1920. She is one of the patron saints of France, along with St. Denis, St. Martin of Tours, St. Louis IX, and St. Theresa of Lisieux.

The Final Footprint – Joan’s ashes were cast into the Seine. A monument in Rouen dedicated to her is inscribed with the words of André Malraux: “O Jeanne, without sepulchre, without portrait, you know that the tomb of heroes is the heart of the living.” A statue in her honor was erected in the Notre Dame de Paris Cathedral, interior. Twenty-five years after the execution, Pope Callixtus III examined the trial, pronounced her innocent and declared her a martyr. Joan of Arc was beatified in 1909 and canonized in 1920. She is one of the patron saints of France, along with St. Denis, St. Martin of Tours, St. Louis IX, and St. Theresa of Lisieux.

On this day in 1640, Flemish Baroque painter, Pieter Paul Rubens died in Antwerp at the age of 62 from heart failure, which was a result of his chronic gout. born in Siegen in Germany on 28 June 1577.

On this day in 1640, Flemish Baroque painter, Pieter Paul Rubens died in Antwerp at the age of 62 from heart failure, which was a result of his chronic gout. born in Siegen in Germany on 28 June 1577.

On this day in 1744, English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer and for his use of the heroic couplet, Alexander Pope died at the age of 56 in his villa in Twickenham surrounded by friends.

On this day in 1744, English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer and for his use of the heroic couplet, Alexander Pope died at the age of 56 in his villa in Twickenham surrounded by friends.

On this day in 1778, French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, freedom of expression, free trade and separation of church and state, Voltaire died in Paris at the age of 83. Born François-Marie Arouet in Paris either on 21 November 1694 or 20 February 1694. Voltaire was a versatile writer, producing works in almost every literary form, including plays, poems, novels, essays, and historical and scientific works. He wrote more than 20,000 letters and more than 2,000 books and pamphlets. He was an outspoken advocate, despite the risk this placed him in under the strict censorship laws of the time. As a satirical polemicist, he frequently made use of his works to criticize intolerance, religious dogma, and the French institutions of his day.

On this day in 1778, French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, freedom of expression, free trade and separation of church and state, Voltaire died in Paris at the age of 83. Born François-Marie Arouet in Paris either on 21 November 1694 or 20 February 1694. Voltaire was a versatile writer, producing works in almost every literary form, including plays, poems, novels, essays, and historical and scientific works. He wrote more than 20,000 letters and more than 2,000 books and pamphlets. He was an outspoken advocate, despite the risk this placed him in under the strict censorship laws of the time. As a satirical polemicist, he frequently made use of his works to criticize intolerance, religious dogma, and the French institutions of his day. The Final Footprint – Because of his well-known criticism of the Church, which he had refused to retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial, but friends managed to bury his body secretly at the Abbey of Scellières in Champagne before this prohibition had been announced. His heart and brain were embalmed separately. On 11 July 1791, the National Assembly of France, which regarded him as a forerunner of the French Revolution, had his remains brought back to Paris to enshrine him in the Panthéon. It is estimated that a million people attended the procession, which stretched throughout Paris. There was an elaborate ceremony, complete with an orchestra, and the music included a piece that André Grétry had composed specially for the event. A widely repeated story, that the remains of Voltaire were stolen by religious fanatics in 1814 or 1821 during the Pantheon restoration and thrown into a garbage heap, is false. Such rumours resulted in the coffin being opened in 1897, which confirmed that his remains were still present. Other notable Final Footprints at the Panthéon include: Louis Braille, Pierre and Marie Curie, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, André Malraux, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Émile Zola.

The Final Footprint – Because of his well-known criticism of the Church, which he had refused to retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial, but friends managed to bury his body secretly at the Abbey of Scellières in Champagne before this prohibition had been announced. His heart and brain were embalmed separately. On 11 July 1791, the National Assembly of France, which regarded him as a forerunner of the French Revolution, had his remains brought back to Paris to enshrine him in the Panthéon. It is estimated that a million people attended the procession, which stretched throughout Paris. There was an elaborate ceremony, complete with an orchestra, and the music included a piece that André Grétry had composed specially for the event. A widely repeated story, that the remains of Voltaire were stolen by religious fanatics in 1814 or 1821 during the Pantheon restoration and thrown into a garbage heap, is false. Such rumours resulted in the coffin being opened in 1897, which confirmed that his remains were still present. Other notable Final Footprints at the Panthéon include: Louis Braille, Pierre and Marie Curie, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, André Malraux, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Émile Zola. On this day in 1814, first wife of Napoléon Bonaparte, and thus the first Empress of the French, Joséphine de Beauharnais died of pneumonia in Rueil-Malmaison, four days after catching cold during a walk with Tsar Alexander in the gardens of Malmaison, at the age of 50. Born Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie in Les Trois-Îlets, Martinique to a wealthy white Creole family that owned a sugar plantation. Her first husband Alexandre de Beauharnais was guillotined during the Reign of Terror, and she was imprisoned in the Carmes prison until her release five days after Alexandre’s execution. Through her daughter, Hortense, she was the maternal grandmother of Napoléon III. Through her son, Eugène, she was the great-grandmother of later Swedish and Danish kings and queens. The reigning houses of Belgium, Norway and Luxembourg also descend from her. She did not bear Napoleon any children; as a result, he divorced her in 1810 to marry Marie Louise of Austria. Joséphine was the recipient of numerous love letters written by Napoleon, many of which still exist. Her Château de Malmaison was noted for its magnificent rose garden, which she supervised closely, owing to her passionate interest in roses, collected from all over the world.

On this day in 1814, first wife of Napoléon Bonaparte, and thus the first Empress of the French, Joséphine de Beauharnais died of pneumonia in Rueil-Malmaison, four days after catching cold during a walk with Tsar Alexander in the gardens of Malmaison, at the age of 50. Born Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie in Les Trois-Îlets, Martinique to a wealthy white Creole family that owned a sugar plantation. Her first husband Alexandre de Beauharnais was guillotined during the Reign of Terror, and she was imprisoned in the Carmes prison until her release five days after Alexandre’s execution. Through her daughter, Hortense, she was the maternal grandmother of Napoléon III. Through her son, Eugène, she was the great-grandmother of later Swedish and Danish kings and queens. The reigning houses of Belgium, Norway and Luxembourg also descend from her. She did not bear Napoleon any children; as a result, he divorced her in 1810 to marry Marie Louise of Austria. Joséphine was the recipient of numerous love letters written by Napoleon, many of which still exist. Her Château de Malmaison was noted for its magnificent rose garden, which she supervised closely, owing to her passionate interest in roses, collected from all over the world.

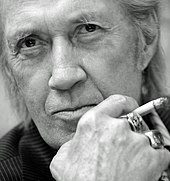

On this day in 2010, actor, screenwriter, director and photographer, Dennis Hopper, died at his home in the coastal Los Angeles district of Venice at the age of 74 from prostate cancer. Born Dennis Lee Hopper on 17 May 1936 in Dodge City, Kansas. He appeared in an impressive list of great, even iconic movies, including: as a goon in Rebel without a Cause (1955) starring James Dean; as Jordan Benedict III in Edna Ferber’s Giant (1956) with Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor and James Dean; as Dave Hastings in The Sons of Katie Elder (1965) with John Wayne and Dean Martin; as Babalugats in Cool Hand Luke (1967) with Paul Newman, Strother Martin and George Kennedy; as the Prophet in Hang ’em High (1968) with Clint Eastwood; as Billy in Easy Rider (1969) which he directed and co-wrote with Peter Fonda and Terry Southern and which he starred in with Fonda and Jack Nicholson; as Moon in True Grit (1969) with John Wayne, Glen Campbell, Kim Darby, Robert Duvall and Strother Martin; as a photojournalist in Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness (1902), Apocalypse Now (1979) with Marlon Brando, Martin Sheen and Robert Duvall; as Frank Booth in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) with Kyle MacLachlan and Isabella Rossellini; as Shooter in Hoosiers (1986) with Gene Hackman; as Lyle from Dallas in Red Rock West (1993) with Nicholas Cage and Lara Flynn Boyle; as Clifford Worley in True Romance (1993) which was written by Quentin Tarrantino and featured Christian Slater, Patricia Arquette, Val Kilmer, Gary Oldman, Brad Pitt and Christopher Walken; as Howard Payne in Speed (1994) with Sandra Bullock and Keanu Reeves.

On this day in 2010, actor, screenwriter, director and photographer, Dennis Hopper, died at his home in the coastal Los Angeles district of Venice at the age of 74 from prostate cancer. Born Dennis Lee Hopper on 17 May 1936 in Dodge City, Kansas. He appeared in an impressive list of great, even iconic movies, including: as a goon in Rebel without a Cause (1955) starring James Dean; as Jordan Benedict III in Edna Ferber’s Giant (1956) with Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor and James Dean; as Dave Hastings in The Sons of Katie Elder (1965) with John Wayne and Dean Martin; as Babalugats in Cool Hand Luke (1967) with Paul Newman, Strother Martin and George Kennedy; as the Prophet in Hang ’em High (1968) with Clint Eastwood; as Billy in Easy Rider (1969) which he directed and co-wrote with Peter Fonda and Terry Southern and which he starred in with Fonda and Jack Nicholson; as Moon in True Grit (1969) with John Wayne, Glen Campbell, Kim Darby, Robert Duvall and Strother Martin; as a photojournalist in Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness (1902), Apocalypse Now (1979) with Marlon Brando, Martin Sheen and Robert Duvall; as Frank Booth in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) with Kyle MacLachlan and Isabella Rossellini; as Shooter in Hoosiers (1986) with Gene Hackman; as Lyle from Dallas in Red Rock West (1993) with Nicholas Cage and Lara Flynn Boyle; as Clifford Worley in True Romance (1993) which was written by Quentin Tarrantino and featured Christian Slater, Patricia Arquette, Val Kilmer, Gary Oldman, Brad Pitt and Christopher Walken; as Howard Payne in Speed (1994) with Sandra Bullock and Keanu Reeves.

On this day in 2012, guitarist, songwriter and singer, 7x Grammy Award winner, Doc Watson died at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina at the age of 89. Born Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson on 3 March 1923 in Deep Gap, North Carolina. He was predeceased by his son Merle who died in a tractor accident at their farm. One of my favorite Guy Clark songs, “Dublin Blues”, has a line that pays tribute to Watson:

On this day in 2012, guitarist, songwriter and singer, 7x Grammy Award winner, Doc Watson died at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina at the age of 89. Born Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson on 3 March 1923 in Deep Gap, North Carolina. He was predeceased by his son Merle who died in a tractor accident at their farm. One of my favorite Guy Clark songs, “Dublin Blues”, has a line that pays tribute to Watson:

The Final Footprint

The Final Footprint